Summary:

Research recommendations often fail to reach users. Without tracking adoption, teams rely on hope instead of evidence to confirm their work creates change.

Many research teams do good work. They identify the right problems, recruit the right participants, and run studies that reveal what is really going on. The end product is often packaged as “insights,” a term that sounds valuable, is easy to celebrate, and has even become part of many team names.

The trouble is, insights themselves do not change anything. They describe the problem and perhaps even provide ideas for how to solve it, but they do not actually fix it.

Too often, the researcher’s work is stopped after describing what is wrong. Their report is shared, heads nod in agreement, and then the project is closed. The assumption is that meaningful changes will follow. But, when the same problems appear in study after study, it is a clear signal that something is breaking between the delivery of research and the delivery of change.

The Gap Between Recommendations and Adoption

When the process is working, researchers’ recommendations transition from insights into specific fixes that improve the user experience. Too often, however, the process falls apart, and there is a void between recommendations and real outcomes.

This gap is where hope likes to lurk. We hope stakeholders will act. We hope they will prioritize the right things. We hope the evidence will be enough. But if you are relying on hope, you are setting yourself up to be fooled. Without proof that your recommendations materialized into the product, you can only hope that your work created change and wasn’t just a compelling but disposable story.

Breakage: The Retail Analogy

Retailers use the term “breakage” to describe products that are damaged before they reach the customer. Sometimes the damage is obvious, like a cracked phone screen or a dented washing machine. Other times, it is invisible, like electronics fried in transit or clothing ruined by humidity in storage. Either way, the outcome is the same. The value is gone before it ever reaches the customer.

In UX research, breakage works the same way — when the value created through recommendations never reaches the user. Somewhere between the readout and the release, the recommendation gets lost, watered down, deprioritized, or even ignored.

You have probably seen versions of this:

- A product owner thanks you for the work, then cherry-picks the one recommendation that already matches their plan and leaves the rest behind.

- A designer starts from your guidance and reshapes it into something that looks modern, but fails to address the root problem that users showed you.

- A developer pushes your fix into a backlog during sprint crunch. It sits there long enough to be forgotten, then is quietly closed during a housekeeping sweep.

- An executive quotes your findings in an all-hands meeting but cannot name a single change that came out of them.

- A researcher assumes someone else owned the followup and moves on to the next project, never confirming what actually shipped.

In retail, broken inventory gets written off as a loss. In research, broken recommendations waste time, money, and opportunity. They also hurt researchers by degrading motivation and collectively harm the UX research profession. But the worst part is that the people paying the emotional toll are the humans using an inferior version of your product.

The Chain Reaction of Breakage

Breakage rarely stops at a single missed fix. It sets off a chain reaction.

One ignored recommendation leaves a major friction point unresolved. Users keep dropping out of a sensitive key flow, and adoption of a related feature never gets off the ground. The product team, confused by poor metrics, launches a separate engagement initiative to treat the symptom. Marketing gets pulled in to craft messages to boost the feature. Engineering burns cycles on nudges and notifications. Meanwhile, the original root cause is still blocking people. Money is spent, time is burned, and credibility quietly erodes.

In postmortems, leaders often ask why nothing moved the needle. The honest answer is simple. The needle was never attached to the change that mattered. The research identified it. The recommendation said what to do. The organization did something else, or nothing at all.

Why Breakage Persists

Most breakage is not intentional. It is the byproduct of how work gets done under pressure. Competing priorities push fixes down the list. Silos separate the people who feel the pain from the people who can fix it. Deadlines reward what is ready to go, not what is necessary to ship. Design and development teams reinterpret recommendations into what they know how to build quickly. Ownership gets fuzzy, and fuzzy ownership is where recommendations go to die.

Breakage thrives when no one measures adoption. Teams may feel productive because features keep shipping, but users are still surprised when their problems remain unsolved.

The Absurdity of Hope

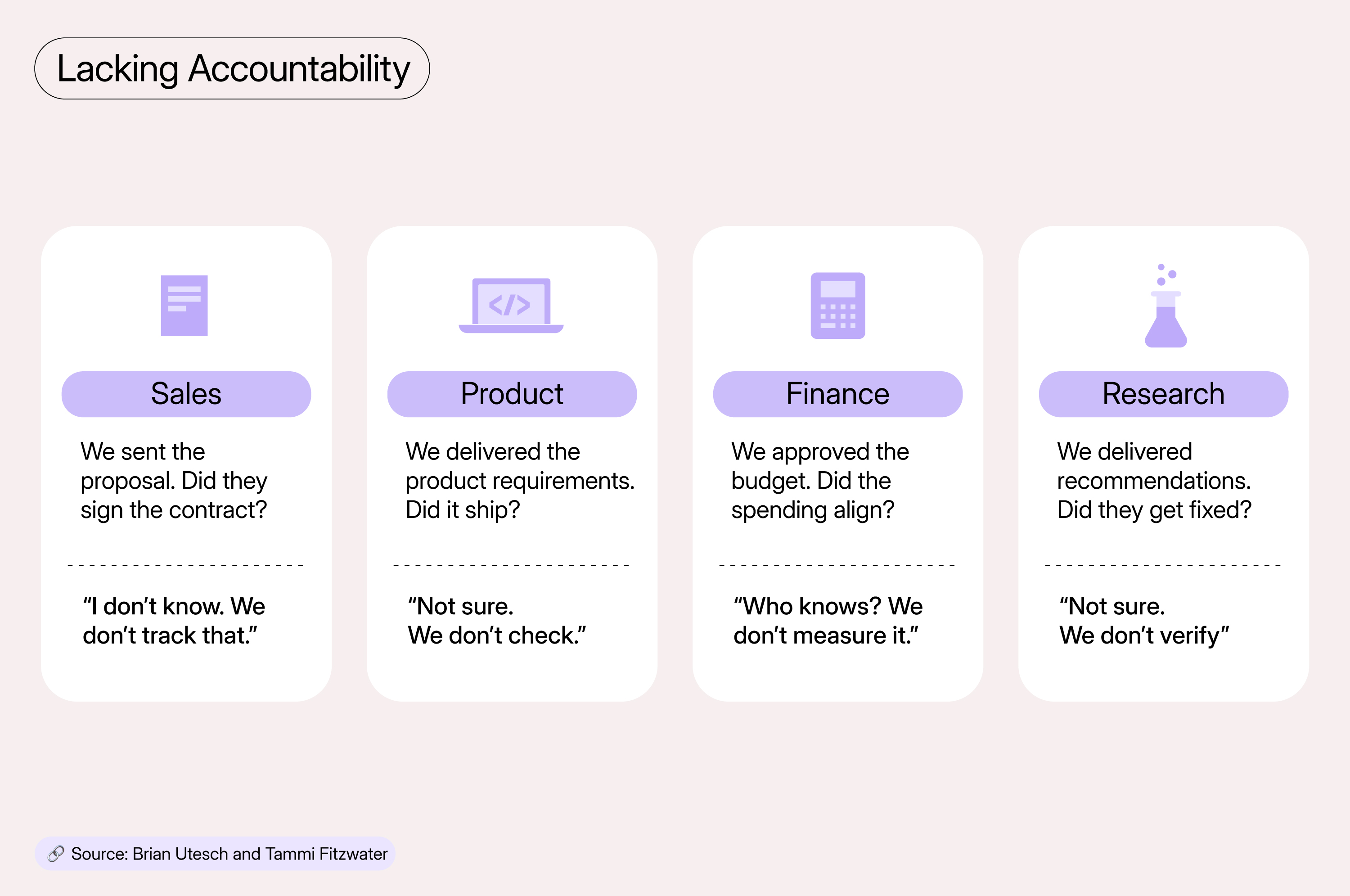

In most parts of business, hope is not a plan. Sales does not pitch to clients and hopes to close without checking conversion rates. Product teams do not list features on a roadmap and hope they materialize without tracking delivery. Finance does not approve a budget and then hopes spending is compliant.

Yet in UX research, many still deliver findings and hope adoption will happen. That is how breakage hides in plain sight. It is convenient to assume that smart people will do the right thing. But assumptions do not ship features. Assumptions do not remove blockers for users. Assumptions protect the organization from discomfort, not the user from pain.

The Emotional Toll on Researchers

Breakage costs users and organizations, but it also drains researchers.

Doing research is not what burns people out. The work can be demanding, but it is meaningful. What burns people out is running the same study again because the first one did not lead to change. It is hearing the same user quote three quarters in a row and knowing it will show up again next quarter. It is telling a clear story and watching it turn into a vague action item that never lands. It is being asked to validate decisions that were made without the user and then being told to bring more data when the existing evidence already points to the fix.

After a while, it feels like shouting into a void. People start to disengage. They simplify reports because they expect the hard parts to be ignored. They stop pushing for the right solution because they are tired of hearing that it is not the right time. It is not the complexity of the research that wears people down. Instead, it is the lack of movement on the user problems that their work uncovers.

If you want to protect your researchers, you have to protect their belief that evidence leads to action.

Why We Need to Track Breakage

In retail, tracking breakage shows where value leaks out of the supply chain. In research, tracking breakage shows where the value of recommendations leaks out of product delivery.

It shifts the conversation from “Did we learn something?” to “Did we do something?” Without tracking breakage, you cannot tell the difference between teams that follow through, teams that cherry-pick, and teams that quietly ignore research.

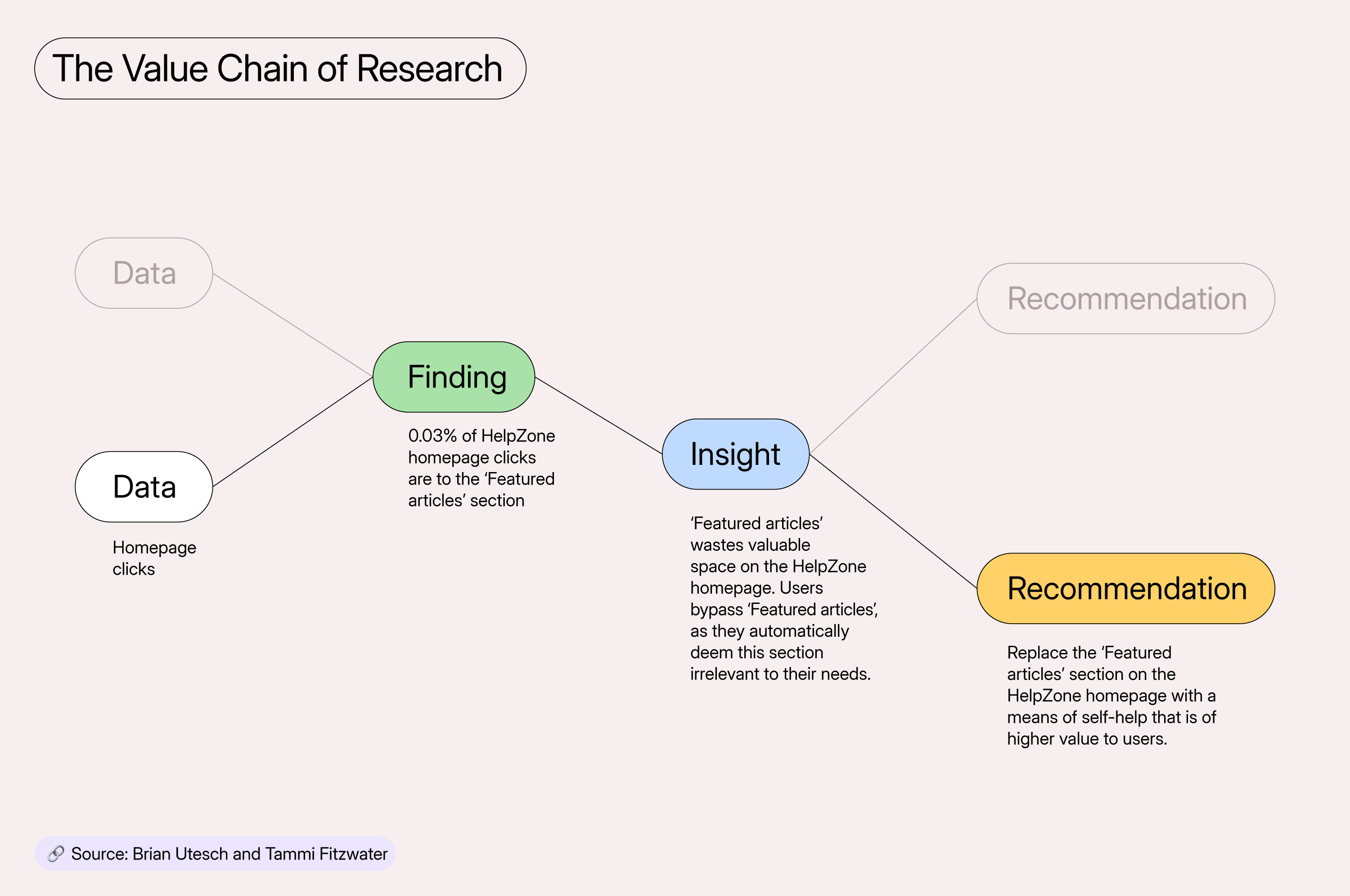

This matters because every recommendation rests on a chain of evidence. Data leads to findings, which build insights, which justify recommendations. If the recommendation never reaches the user, the entire chain is broken. It does not matter how rigorous the study was, how compelling the findings were, or how sharp the insight sounded. Until a recommendation is adopted, the chain is incomplete.

Tracking breakage makes the weak points in that chain visible. Were the data solid, but the finding diluted when translated to stakeholders? Maybe the insight was clear, but the recommendation was reshaped to fit a familiar design pattern that did not address the root cause. Or perhaps the recommendation was sound but deprioritized in delivery because it did not have an executive sponsor.

Without measuring breakage, those points of failure stay hidden. When breakage is tracked and exposed, you can finally see whether the chain is intact all the way through to impact.

Practical Signals That Breakage Is Happening

There are early signals that tell you breakage is occuring even before you formally measure it.

You’ll see:

- Teams asking for “just one more round” without defining what new evidence would change the decision

- Readouts where the most important recommendation gets presented like a footnote because it is politically inconvenient

- Designers quietly bypass the recommendation for a pattern library solution that is easier to ship but does not solve the underlying problem

- A flurry of documentation with no corresponding tickets, no owner, and no release plan

- Leaders reference the research in broad terms without being able to point to a change that reflects it

You also see subtle social cues. People stop asking the researcher to attend planning meetings. Updates mention research in the past tense, as if the point of the work was awareness rather than change. The researcher hears about a release only after the fact, when a user support ticket exposes that the core problem was not addressed.

None of these on their own indicate breakage, but together they paint a clear picture. Value is created by research. Value gets lost in delivery.

A Short Example

Consider a checkout flow that was bleeding revenue because users could not understand shipping rules. The research showed the exact moment of confusion and proposed a clear redesign that explained the rules in plain language, removed a misleading toggle, and added a simple preview.

Afterthe research results were communicated, three things happened:

- The team adopted the copy change because it wasquick.

- The toggle removal was deferred because another team owned the related logic.

- The preview was redesigned into a tooltip that appeared only on hover and disappeared on mobile.

On the dashboard, the team reported progress. Copy improved. The tooltip shipped. Meanwhile, the dropoff rate barely moved because the misleading toggle still blocks understanding, and the tooltip fails on mobile.

A quarter later, leadership asks for a new study. The researcher runs it. Users repeat the same pain. The recommendation repeats with the same priorities. Everyone feels déjà vu.

What would have helped is not more data. Instead, what is needed is the discipline of tracking whether the original recommendations made it through to delivery without breakage. In this case they did not.

What Tracking Breakage Reveals

Once you track breakage consistently, patterns emerge. You see which teams follow through on high-value recommendations versus teams that only fix low-friction tasks. You see the project stages where recommendations tend to break. Some organizations lose the thread during prioritization. Others lose it during design reinterpretation. Others lose it during development crunch when the scope gets trimmed without revisiting user risk.

You also start to see where your time is best spent. If a team consistently ignores high-value recommendations, you can stop pouring energy into more studies and shift effort toward influencing the blockers that prevent adoption. If a team consistently adopts but needs help prioritizing, you can focus on impact framing and sequencing over raw volume.

None of this requires blaming individuals. It requires treating adoption like any other important outcome. You define it. You track it. You respond when it is not happening.

Where We Go Next

Recognizing breakage is only the first step. The harder part is measuring it in a way that is structured, credible, and resistant to spin. Our next article in this series introduces a metric that can do just that — track breakage in a credible way. We call this the Recommendation Adoption Score (RAS). We’ll explain what the RAS is, how it is calculated, and how it gives researchers and leaders a shared way to talk about adoption without hiding behind vague claims or empty promises.

Key Takeaways

- Insights are not enough. The real test of research is whether recommendations make it to users.

- Hope is not a strategy. Without tracking adoption, you are relying on assumptions, not evidence.

- Breakage — when recommendations get lost, diluted, or ignored — is as costly in research as it is in retail.